Warner Bros. Wonder Woman opened June 2, but the character debuted over 70 years ago and has roots that should make us pay more attention not only to the unfairly maligned “first-wave feminists,” but also the generation that emerged between the two imperialist wars. I have not seen the film yet, so this is in no way a spoiler or even a review. Call it a preview, or an alternate view of her radical origins in the years between World War I and World War II. Like a lot of young people of my and other generations, Wonder Woman catches the imagination, but I hope her origins capture our radical imagination as well.

In George Bernard Shaw’s preface to his 1920 play, Back to Methuselah, written just after and in response to World War I, Shaw puts the political establishment responsible for “The Great War” in his crosshairs. He considers deficient the standard remedies to their bad behavior – religion and education – and further notes that it has taken two of the most brilliant political tacticians of his day, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, over 40 years of research to produce salient political treatises. How, Shaw wonders, can we expect better from our contemporary legislators who have devoted no time at all to the subject? He also takes Darwin to task and what lessons nation-states drew from him, in err.

Shaw is angry. He is thinking about the carnage that just ended and indicts the guilty on all sides. He had stirred controversy during the war when he suggested the soldiers on both sides turn their weapons on their own generals, shoot them, and come back home for Christmas. In his Preface, he assesses:

“Britain, Germany, France, and the United States of America could have imposed peace on the world, and nursed modern civilization in Russia, Turkey, and the Balkans. Every meaner consideration should have given way to this need for the solidarity of the higher civilization. What actually happened was that France and England, through their clerks the diplomatists, made an alliance with Russia to defend themselves against Germany; Germany made an alliance with Turkey to defend herself against the three; and the two unnatural and suicidal combinations fell on one another in a war that came nearer to being a war of extermination than any wars since those of Timur and Tartar; whilst the United States held aloof as long as they could, and the other states either did the same or joined in the fray through compulsion, bribery, or their judgment as to which side their bread was buttered.”

It’s hard for us to imagine those post-war days and the impact it had on a generation of writers and militants, but also the impact it had on making a generation of factory workers, sharecroppers, and Pullman porters into writers and militants. For us today, the post-World War I generation is mostly a blur that comes into focus with the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler.

But that post-war generation was a radical time, and this affected Wonder Woman and her inventor, William Marston Moulton. It was a time that inspired such disparate personalities as IWW organizer and Socialist Party member Margaret Sanger to organize labor strikes; or, some returning Black American war veterans, like Haywood Hall, better known as Harry Haywood, who first formed the African Blood Brotherhood, a militant Marxist organization whose membership later merged with the new Communist Party USA by the early 1920’s.

Inspired by women like Emmeline Pankhurst, the British suffragist who was taking the cause of voting rights for women to increasingly militant confrontations, Marston began to despair as much for patriarchy as his contemporary Shaw despaired for capitalism.

Pankhurst’s appearance in Boston in 1911 has an interesting footnote: besides a young Marston in the large audience, a young Connecticut couple was present. The couple was Thomas and Katharine Hepburn. Mrs. Hepburn had earned an MA from Radcliff College and found rearing children kind of a bore, so her husband took her to hear Pankhurst, and this lit the fire of Mrs. Hepburn not only to immersing herself in the cause of women’s suffrage, but also cofounding Planned Parenthood with Sanger and becoming a Marxist. The couple were the parents of the actress of the same name.

William Moulton Marston, the inventor of “The Wonder Woman,” as he called her, was no ordinary Harvard PhD. Some biographies credit him with being the actual inventor of the Polygraph; others write he invented the mechanism with which the Polygraph was made. Marston himself says he invented it to prove to women that men were cheating on them. Regardless, he was not only changed by the carnage of WWI, like Shaw, Sanger, and Haywood, but also, like Shaw, he was moved to indict systems and ways of thinking. Marston concluded that patriarchy would destroy humanity and that our only salvation was matriarchy headed by liberated women and subjugating ourselves to their rule.

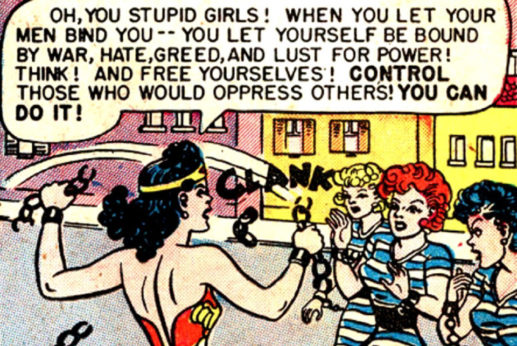

Prof. Marston could not get his doctrine into many classrooms because he couldn’t keep a job at any of the colleges that hired him. He probably wasn’t a bad teacher, though later events would indicate he was a stubborn one to his ideas and not receptive to the official narratives endorsed by our best bourgeois institutions of higher learning. The nearly two decades he guided the Wonder Woman comic were 20 years of battling censors over bondage scenes and hints of lesbianism. But this stubborn streak didn’t keep him off the tenure track, his own lifestyle did.

Marston lived openly with two women with whom he had several children. This was too much for the 1930s, and when college administrations found out, so was his contract. His first wife, Elizabeth, was a practicing attorney. The other woman he fell in love with, Olive, was not only a student of his, but also the daughter of Ethel Byrne, Margaret Sanger’s older sister and another cofounder of Planned Parenthood. Sanger’s niece moved in to the Marston home, and collectively a family was raised.

Sensation Comics saw this Harvard man as cachet. Marston saw them as a better venue to spread his “propaganda” (his word, not mine). He wanted to convince people of the impossibility of patriarchy, the inability of men to rule, and their untruthfulness. Wonder Woman was his vehicle. I’ve read no connection, but I often wonder if given the circles Marston ran in, “The Wonder Woman” had any relation in title to Shaw’s pre-war play, “Man and Superman,” where the bride chooses the revolutionary to marry.

The background mythology of Marston’s Wonder Woman is instructive here. Borrowing from first-wave radical feminist texts, like Charlotte Perkins Gilman, he wove a tale of women in some vague region of the Mediterranean who were slaves of men and freed through the intervention of Aphrodite. Freed, they were tricked back in to slavery. Aphrodite frees them yet again, but this second time the goddess mandates the Amazons wear forever the emblems of their captivity – those famous bracelets – so as not to be tricked again. The goddess relocates them on a remote island where procreation is achieved when clay figures are “breathed into life” by Aphrodite herself.

This is how the Amazon queen’s daughter, Diana, is born.

When, during the war, Steve Trevor, a major, crashes a plane, it’s a setup to his being a foil, a fool. But the carnage of the war that made men like Shaw so mad or aroused a new militancy in Black soldiers convinces the Amazon queen that not only this man needs to be taken back but also the war has to be ended before the planet is destroyed. Unlike the sexual tension between Wonder Woman and Trevor in later comics, under Marston, the major was a bit of a buffoon, making frequent advances on Diana and being jujitsu-moved to the floor.

Diana’s headband is a version of a tiara to signify her royal blood, and she was no damsel in distress. She was a potent icon whose imagery alluded much to earlier suffragist writings. This was not coincidence. The illustrator Marston insisted upon had been an illustrator for some radical suffragist publications in the early 1900s.

All in all, unlike contemporary comics of the 1940s, Wonder Woman has to be placed within the radical tendencies of the often-overlooked post-WWI period and the men and women who were agitating and organizing for real, anti-militarist, anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal change. This is why we should never dismiss those first-wave feminists for their lack of racial diversity. Of course, we can’t ignore it either. But the breadth of their efforts includes long-lasting institutions, like Planned Parenthood, and pop-icons, like Wonder Woman. These contributions deserve study and our appreciation.

Comments